Denmark is known as one of the world’s most secular and liberal democracies. But the Danish Parliament will likely soon pass a law that will punish Danes with up to two years in prison if they engage in the “improper treatment of scriptures of significant religious importance to a recognized religious community.”

A bill currently being debated (and expected to pass) has been revised to limit some of the collateral damage to free expression since its first introduction in August. But even in its revised form, the bill is likely to criminalize certain artistic and political protests against religious fundamentalism.

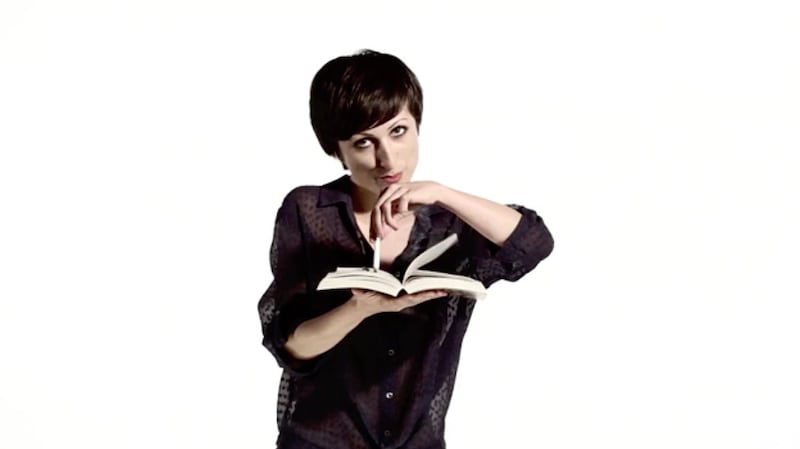

This includes the Danish-Iranian artist Firoozeh Bazrafkan, who risks going to prison if she persists with her performative art pieces that have included shredding, whipping, and branding the Quran as a protest against Iran's theocratic regime.

ADVERTISEMENT

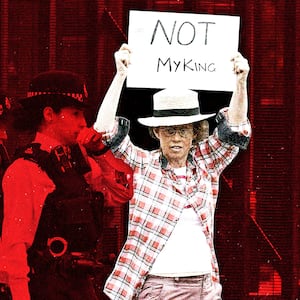

A still from an art piece by Firoozeh Bazrafkan called Cigarette Burn.

Firoozeh Bazrafkan/VimeoMore broadly, the Danish government’s reintroduction of the crime of blasphemy marks a watershed in Danish history. No Dane has been convicted for blasphemy since 1946 and the blasphemy ban was repealed in 2017.

When a Danish newspaper published cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad in 2005, successive Danish governments stood firm when authoritarian governments and religious extremists demanded that the newspaper and editors be punished by the authorities. As such, the bill is likely to have global ramifications by emboldening the very authoritarian states and incentivizing religious extremists whose censorial demands were rebuffed in 2005, and who will view the Danish volte-face as a significant win.

The current political backdrop of the government’s bill is the numerous Quran burnings carried out by far-right demonstrators. These Quran burnings have led to coordinated diplomatic pressure against Denmark by the 57-member-state Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) as well as real threats from jihadist groups like al Qaeda.

There has been limited domestic pushback against the bill, since large parts of the Danish population are sick and tired of the police spending significant resources on protecting extremist demonstrators who go out of their way to provoke hostile reactions against Denmark at home and abroad.

A Quran is burned by an activist from the small right-wing group, Danish Activists, on July 28, 2023 in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Ole Jensen/Getty ImagesIt is perhaps also a sign of democratic maturity that most Danes instinctively recoil at the idea and sight of book burnings. For centuries, authoritarians have used the burning of books, which they deem "degenerate," as a symbolic act to cleanse society and label opponents as enemies of the state. The most notorious example was the Nazi mass burning of some 40,000 “un-German” books across Germany in 1933, which preceded the establishment of an unforgiving totalitarian and genocidal dictatorship.

But the use of state power to seize and burn books on a vast scale, to enforce censorship and instill fear, is different from individuals who burn books as a peaceful symbolic protest against institutions, governments, religions, or ideologies.

When it comes to Nazi Germany, the most relevant question to ask is not whether the Nazis burned banned books, but what did the Nazis do to people who burned or desecrated canonical Nazi literature or symbols? As the British historian Richard Evans has put it, anyone who tried to burn Mein Kampf in 1933 “would have been arrested and shot.”

When delving deeper into history, it’s also clear that burning books or symbols has been an essential form of protest, utilized by individuals and groups to make powerful statements or advocate for change.

The German Christian reformer Martin Luther’s defiant act in 1520 illustrates this point. The influential reformer, in a blatant display of dissent, burned the papal bull “Exsurge Domine.” This document condemned Luther, labeling him a heretic, and demanded the obliteration of his writings.

The irony here cannot be overlooked—Luther was threatened with excommunication and the destruction of his works, yet he retaliated by setting the papal bull itself ablaze, in a highly symbolic repudiation of the authority of the pope and Catholic Church that resonated deeply across Europe.

Jumping ahead to July 4, 1854, we find another telling instance from American history. William Lloyd Garrison, a radical abolitionist, shocked public opinion when he publicly burned a copy of the U.S. Constitution. Garrison referred to the document as “a covenant with death, and an agreement with Hell.” His fiery critique stemmed from the Constitution’s failure to denounce and prohibit the inhuman institution of slavery.

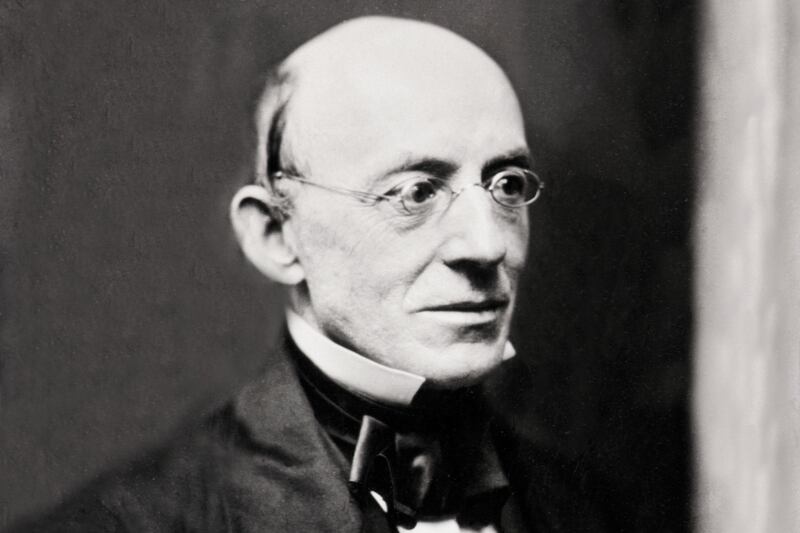

A portrait of William Lloyd Garrison, the American abolitionist who founded the Liberator, a famous anti-slavery journal.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesThe early 20th century offers more examples of the burning of writings and symbols as an expression of protest against injustice.

In 1918, in a show of resistance against the continued denial of women’s right to vote, American suffragettes torched copies of speeches by President Woodrow Wilson. The following year, their protests escalated. Outside the White House, members of the National Woman’s Party burned an effigy of President Wilson and denounced him as “the leader of an autocratic party organization whose tyrannical power holds millions of women in political slavery.” Several of the women involved in the demonstration were arrested.

Suffrage protestors burn a speech by President Wilson at Lafayette Statue in Washington, D.C. in 1918.

Library of Congress

Reporters gathered near CNA pacifists David A. Reed, 19, of Voluntown, Connecticut, David P. O'Brien, 19, of Boston, David Benson, 18, of Morgantown, Virginia and John A. Phillips, 22, of Boston as they burn their draft cards at a Vietnam War protest.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesIn the 1960s the public burning of draft cards became a popular, if deeply controversial, way to protest U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.

In 1984 Gregory Lee Johnson burned the American flag as a protest against the Reagan administration in Dallas, the venue of the Republican National Convention. Johnson was arrested and convicted under a Texas law prohibiting the “desecration of a venerated object.” Five years later, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that the First Amendment protects expressive conduct which includes the right to burn the Stars and Stripes as part of a political protest.

This precedent has proved an important bulwark against government encroachment on protests. As late as 2020, then-President Donald Trump called for criminalizing the burning of the U.S. flag following the nationwide protests after the police killing of George Floyd.

Outside the U.S., persecuted minorities have also resorted to the burning of sacred texts as a means to protest oppression and inequality.

In 1927, the Indian social reformer (who later become the minister of justice) Babasaheb Amebedkar burned the Hindu text of Manusmriti, which prescribes the strict caste-based discrimination that for centuries relegated so-called Indian “untouchables” or “Dalits” to social outcasts facing crippling social inequality. Even today, Indian Dalits celebrate and reenact Amebedkar’s provocative act of defiance as a rejection of persistent discrimination.

These historical accounts underscore a vital distinction: Context matters. The act of burning documents, books, or symbols can signify different things depending on the circumstances.

When carried out by states it is an act of oppression, aimed at silencing dissenting voices. Yet, when done by individuals, it can serve as a powerful form of protest, employed by those looking to challenge prevailing norms and effectuate change.

That is not to say that all peaceful protests that resort to burning books advance equality and justice. More often than not, burning books is a poor and crude substitute for reasoned debate.

But one does not have to agree with the anti-Muslim bigotry of Danish far-right protesters to recognize that permitting the government to shield specific beliefs, ideas, or symbols sets a dangerous precedent. Equality, tolerance, and freedom are ultimately more likely to thrive in countries where the burning of venerable books, symbols, and objects are met with criticism, peaceful protest, and societal rejection than in states where such provocations are sanctioned with punishment and prison.