The received wisdom is that the book has always been the problem with Chess, if only—as so many have attempted—the book could be fixed…

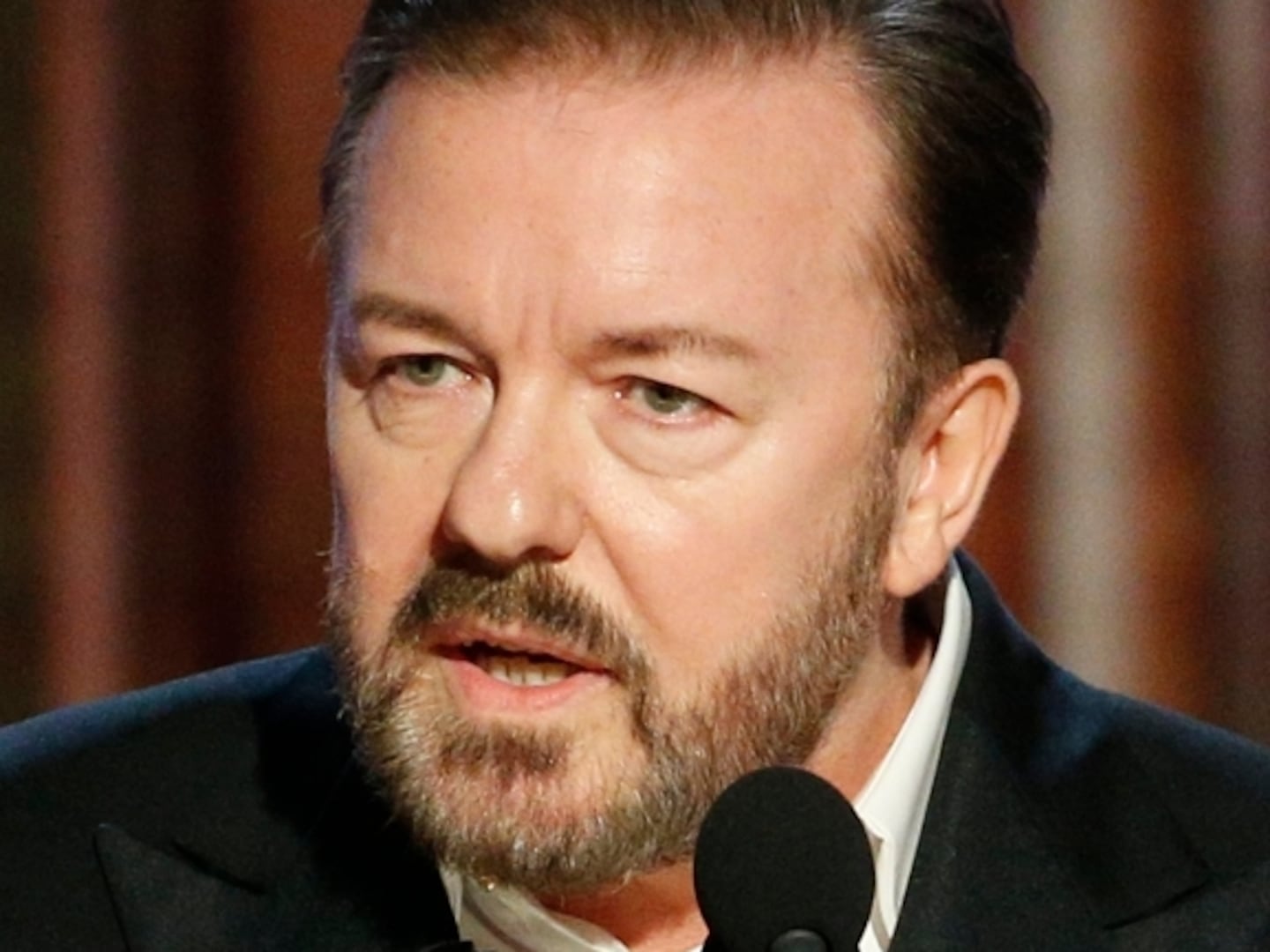

But, as the much-anticipated revival of Sir Tim Rice and Abba’s Benny Andersson and Björn Ulvaeus’ 1986 musical on Broadway reveals, Chess is its own cabinet of curiosities, and it delights in displaying them all on stage in real time as brashly as its two peacocking competitors, the Russian Anatoly Sergievksy (Nicholas Cristopher) and the American Freddie Trumper (Aaron Tveit).

We barely see any chess played between them in this almost three-hour musical endurance test (Imperial Theatre, booking to May 3, 2026). But rather like a chess match, the show (directed by Michael Mayer, with a new book by Danny Strong), stares down each one of its own structural and narrative flaws, fixes the audience with a challenging glare, then makes a series of moves best known to itself to win our attention.

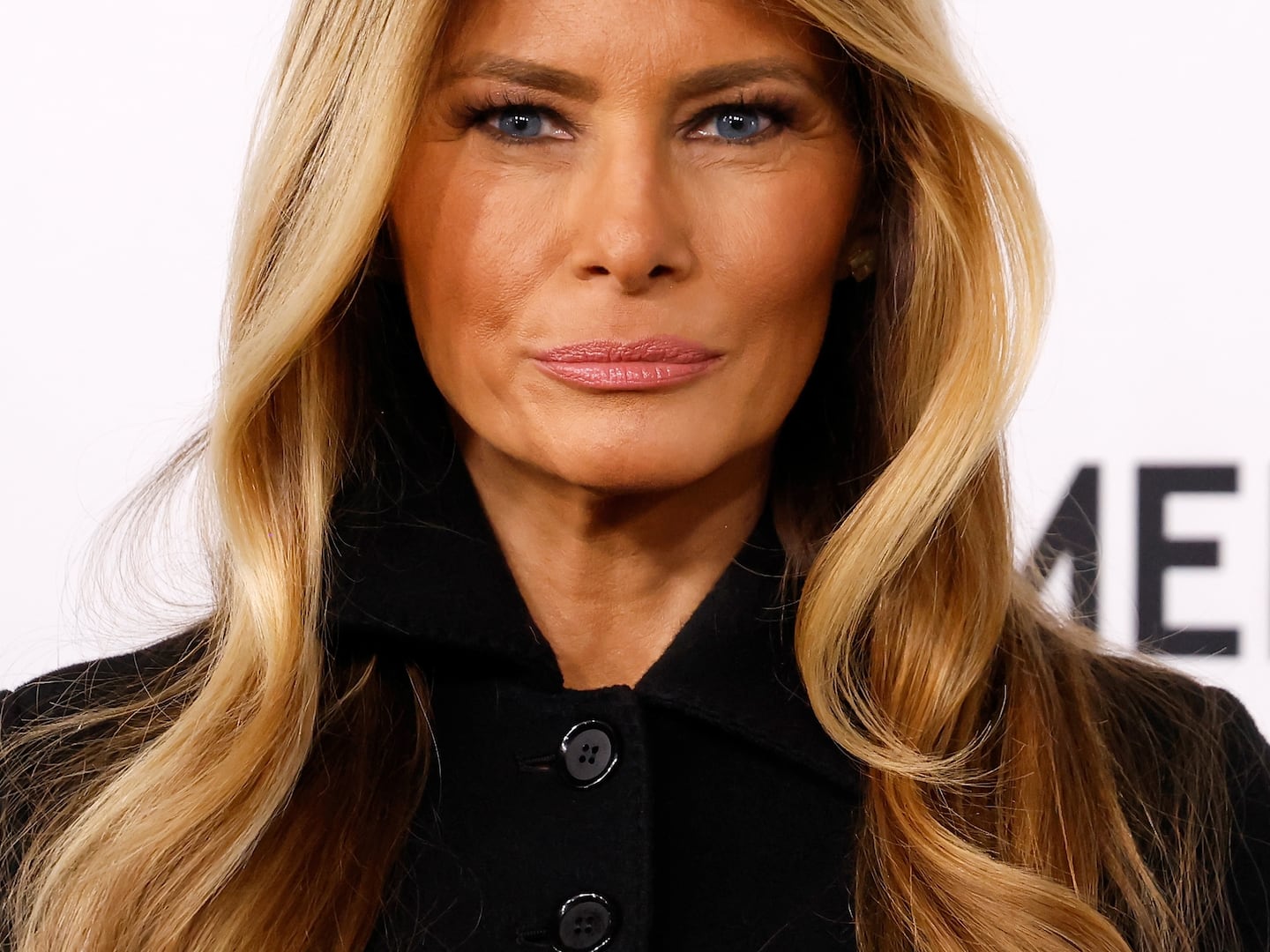

The show—less about chess, more about the possible end of the world because of Russian-American tensions—works in enough fits and starts to cohere, and in a few sung moments to actually thrill, thanks to the go-for-broke commitment of Christopher, Tveit, and Lea Michele as Florence, Freddie’s lover and chess strategist. The trio are differently excellent performers, who try— ultimately in vain—to make Chess’ characters and story intelligible.

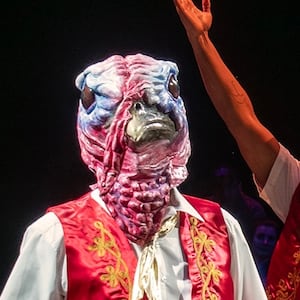

The also-excellent Bryce Pinkham almost upstages them as the Arbiter, who archly narrates events with pointed present-day commentary inserted; his first winking joke is around Tveit’s character’s surname. An ensemble of dancers, when not leaping and thrusting, stay on stage as a leeringly watchful Greek chorus (the razzle, add-more-dazzle choreography is by Lorin Latarro). Musicals who want to know how to end a first act should look no further than Christopher’s thunderously powerful marshaling of “Anthem.”

Perhaps it’s unsurprising that the story has always been this battering ram of a musical’s principal problem. Chess began life not as a musical, but a concept album released in 1984. It remains a redolent creature of the 1980s, with its earnest macro-themes of East-West politics and nuclear perils, and all the unironic hair-tossing, big-emotion, and over-expressive hallmarks of that era’s pop culture. David Rockwell’s geometric set of shifting panels and platforms and Kevin Adams’ primary-colored lights (red for Russia, blue for America) are just as era-specific.

Chess is a pounding, hulking, pop ballad-stuffed leviathan of its time, and this cast go correspondingly, shamelessly big. They are primed to fight, argue, swagger, declare their love, betray, accuse someone else of betrayal, compete for high stakes, threaten, seduce, live or die, win at all costs, risk everything for love, confess everything, lose it all. Rather like a chess board, everything is black or white. Sample lyrics: “The blood, the sweat, the tears/The late, late nights, the early starts/There they go again!/Your deeds enflame them/Drive them wild, but then/Who wants to tame them…”

But while the show’s songs run furiously hot, its characters stay resolutely cold and uninvolving. And, the book—despite Pinkham’s comically authoritative guiding hand—remains a messy puzzle, using the lingering Cold War and 1980s nuclear superpower tensions to implausibly sex up, well, chess.

A drily excellent Sean Allan Krill as CIA agent Walter de Courcey and Bradley Dean as his KGB opposite, Alexander Molokov—both nodding to the plot’s absurdities without capsizing the show—try to fix the matches between Anatoly and Freddie for their countries’ political ends.

These machinations go nowhere, so the musical creates a love triangle between Anatoly, Freddie, and Florence. This too hits a wall, because of a stark lack of chemistry in each coupled combination; all three leads seem independent rather than fatefully yoked together.

As Michele’s lushly assertive belting implicitly shows, Florence doesn’t need either of them, and both men—experiencing different mental health issues—clearly need some time away from playing chess. Who should end up with who? Who cares?

Chess next introduces Svetlana (Hannah Cruz), Anatoly’s wife, long left behind in Russia, to try and win him back from Florence, with the added PR victory of Russia reclaiming one of their own. But this too is a narrative cul-de-sac, because Anatoly immediately says “No,” and the couple again have no chemistry.

What you are left with is two women who would be better off without these men (but of course are given nothing to sing about but men), and people tunefully booming songs about their troubled pasts and how they feel, like Christopher’s “Where I Want to Be,” Tveit’s “Pity the Child,” Michele’s “Nobody’s Side” and “Heaven Help My Heart,” and Cruz’s “He Is a Man, He is a Child.”

The two most famous numbers from the show—the chart-toppers “One Night in Bangkok” and “I Know Him So Well”—are performed well if underwhelmingly, despite Tveit’s charming, scantily clad leadership of the first, and Michele and Cruz’s plaintive rendition of the second. Maybe Elaine Paige and Barbara Dickson benefited from the technical advantages of video, but on stage—with a tinny-sounding orchestra—the dueling, echoing experiences of the two women feel unmoored and de-passioned. (Surprising standouts include the ebullient “Merano” and cheesy Russian song-and-dance number, “The Soviet Machine.”)

Big numbers and baffling story almost spent, Chess leans into the possibility that nuclear war is extremely nigh, and the outcome of a final chess match could kill us all. There is even more personal and political plot within wailed lyrics, a surprise ending that is not only no surprise but also not the emotional wallop the show intends, and songs that make head-scratching sense.

But Chess doesn’t care. It’s here to pulverize you with high-stakes passion, possible global apocalypse, and blazing over-emotion. It is, like many spectacles, good, bad, needily insistent, and unapologetically exhausting. As soon as you buy your ticket, it’s checkmate before you’ve even taken your seat.