Train Dreams is not only the best feature of 2025, it’s one of the decade’s great American films: a stirring tribute to this country and the anonymous men and women who built it; a paean to a fading landscape and a rugged, natural way of life; an elegy about the immediacy and eternity of grief; and a heartbreaking—and yet also hopeful—portrait of impermanence and the cinema’s ability to memorialize that which doesn’t last.

Jockey director Clint Bentley’s sophomore effort, which hits Netflix Nov. 21, is a profound story of an ordinary man—his joys and sorrows, hopes and dreams, hardships and grace—and immediately marks the filmmaker as an artist of tremendous precision, elegance, and acuity.

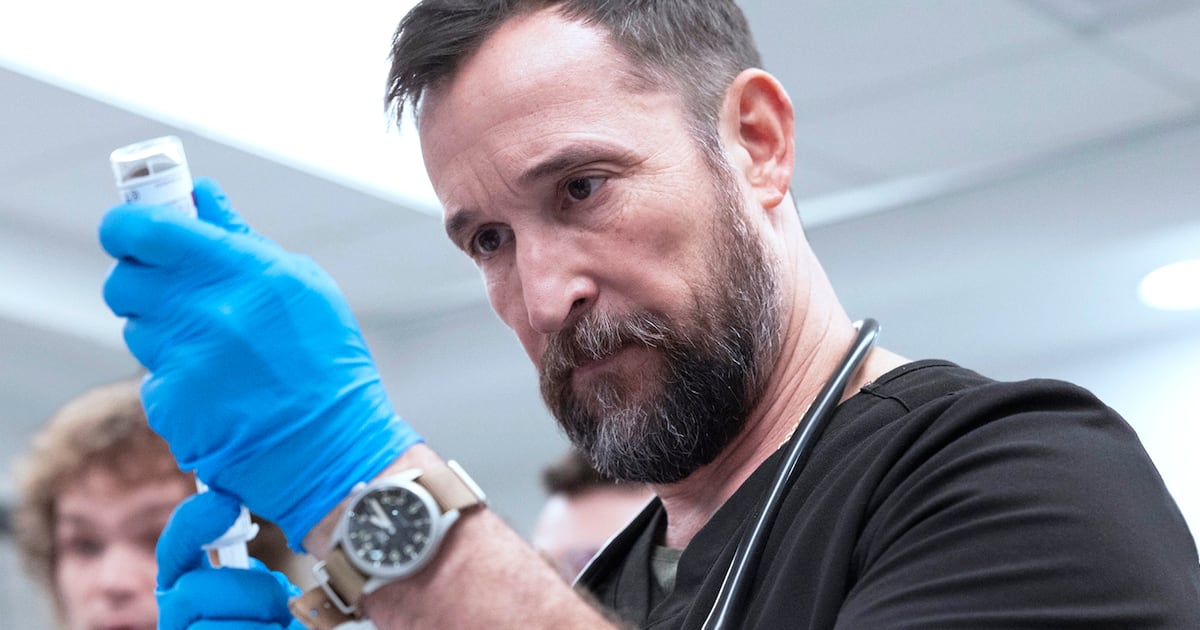

An adaptation of Denis Johnson’s 2011 novella of the same name, it tells the quiet tale of Robert Grainier (Joel Edgerton, in a career-best performance), an early 20th-century logger working in the Pacific Northwest alongside kindred itinerants in order to make a living for himself and his wife Gladys (Felicity Jones), with whom he resides in a log cabin beside a stream with their infant daughter.

His is an existence of arduous toil and extended stretches away from home, cutting down trees to clear the paths, erect the bridges, and provide the wartime materials necessary to sustain and fortify the nation. It’s a day-to-day marked by quiet highs and cavernous lows, the worst of which is brought about by a wildfire which destroys that which he holds most dear and forever alters his course and his heart.

With melancholy lyricism and loveliness, Train Dreams finds wisdom in the smallest of moments, speaking directly and poignantly to the core of the human condition. Through Grainier’s odyssey, it expresses what it means to be alive—and, specifically, how each life is at once destined for obscurity and yet brimming with complexities. A masterfully constructed poem about transience and permanence—both of which define man’s relationship to his simultaneously nurturing and indifferent environment—it’s an awe-inspiring film that itself seems fated to endure as one of the medium’s lasting triumphs.

It’s no surprise, then, that ahead of its streaming debut, we were thrilled to speak with Bentley about his attraction to Johnson’s novella, his collaboration with Edgerton, and his fondness for stories about people, places, and eras on the brink of extinction.

Train Dreams deals with a fundamental truth that most movies don’t: not only does nothing last, but most of us are forgotten. And then it goes one step further and asks, given that, what makes a life valuable? Was there something in your own life, or career, that drew you to that theme?

So you figured you would just start off with the softball question—like, make it super simple at first! [laughs]

We’ll start big and go smaller.

No, it’s great. I’ve talked to some people who read the book who think it’s super depressing, and they don’t see the same thing in it that I do. I think it’s funny that we’re looking at the same text and getting different things from it. Thinking about the movie itself, when I started writing and trying to contend with it, the question was, what am I actually trying to say?

What you just articulated very well is what I hoped people would take from it. This aspect of, yes, life is a bit meaningless. And that’s not even just the regular person. You talk to filmgoers and ask them when was the last time they watched a movie by [F.W.] Murnau, you know? One of the pioneers of cinema and one of the greatest film artists ever, and they may have never watched him. So it’s not even just the average person. Most of us will not be remembered in the way that I think we hope we will be.

I think there’s a bit of a beauty in that. But once you contend with it, you have to say, well, what is meaningful? And it’s those little moments you have in life. The little things, and being present in those moments, actually give your life value and meaning.

Did your own personal experiences inform how you approached the film?I think there’s a lot of things throughout my life [that influenced it]. We started writing this as we were coming out of COVID, and everyone’s life got turned upside-down. I lost a few friends in that time who probably wouldn’t have passed away otherwise. Unrelated to COVID, and right before it, I lost both my parents in quick succession—very, very, very quickly and surprisingly in both cases. And then my first kid was born right around that time.

Plus, as we were writing it, all of this AI stuff started happening as well, where it seems like the people who are pushing these AI developments are also okay with the question of, what is the value of a human life? Not just, should we have lawyers or should we have doctors. More than just the economical aspect of it, but the existential question that seems to be being asked. I think all of that just went into it, and what came out is my viewpoint on the world.

At what point did you decide to adapt Denis Johnson’s novella?

It came after I made Jockey. I’d been a fan of Dennis Johnson’s for a long time. This is actually his first book that I encountered, just because of when it was published. The book was published right around the time I was getting out of college, and after I read it, I was hooked and read almost everything he’d written.I don’t know that I would have had the courage to take on one of his books, and certainly not this one. Producer Marissa McMahon and her team had the rights to the book, and they had been trying to find a filmmaker to make it for a long time. They saw Jockey and thought they saw some sensibility match and asked me if I wanted to adapt it. It felt almost too good to be true.

It’s not, on the surface, a surefire commercial endeavor. How difficult was it to get the film produced?

There was a bit in writing it where part of me thought this might never get made, because nothing about this adds up to something that Hollywood will take a risk on. It needs a certain budget, and it’s got some weird stuff in it that I really wanted to get in. From the beginning, we all talked about how the weird off-kilter stuff is what makes it special. On top of that, I wanted to add some other weird stuff that’s not in the book. So I thought it might not happen. But I was really just finding joy in writing it with Greg [Kwedar].

At a certain point, I thought a lot about what makes a good adaptation, and I felt like I needed to be true to the spirit of the book and to the spirit of what Dennis Johnson had started. But also, I wanted to use the book as a jumping-off point a bit. Not to say anything that was the opposite of what the book was saying, but there are quite a few things I contend with that people who read the novella might say, well, I didn’t get that from the book. For better or worse.

How much research did the film require?

My family was a logging and ranching family, and my uncle was a logger for a long time. So I’d been around that. But obviously, what they did back in the day—the tools they used when Grainier was doing it—was very, very different. That was a really enjoyable part of it. I love researching, and Greg does as well. So as we were writing, we were devouring any book we could find about the time.

What’s funny is, when you go out into Idaho and Washington state and meet people, those logging families have been doing this forever. It wasn’t hard to find logging families who would say, here’s my granddad’s crosscut saw. You could feel the history right there. There are a few scenes in the movie set in this logging camp, and that was Webley Lumber yard in Washington state—an actual logging operation that’s been in that family since the 1800s. They were super excited for us to film there, and all we did was move the modern equipment out and we had the shot.

How did Joel become involved in the film?

Joel was somebody whom I’d always had a massive amount of respect for, not only as an actor but as an artist and what he had done with Blue-Tongue films, seeing him write on friends’ movies and co-write some really amazing scripts, as well as direct his own movies. He felt like a full artist you’d like to have on board with you.

Also, you need this threading-the-needle type actor who is masculine and tough, but also sweet and kind of innocent, and can do so much with his eyes. It required somebody who could be quiet without disappearing into the scene, and you always wanted to know what they were thinking, even if they weren’t saying much. He seemed perfect for it, and he was the right age too. If he had been 10 years older or younger, it wouldn’t have worked; you need somebody you can age up and down. I was tickled to death that he was into it.

When I met him, I remember sensing a boyishness in him when we hung out the first time, after he read the script and we were talking about him maybe doing it. I really wanted to infuse more of that boyishness into the character when Grainier is at home.

When did Felicity enter the equation, and how did you know she and Joel would have such terrific chemistry?

Joel and Felicity had wanted to work together for a long time, and I think they had come close on a couple of films, so I just trusted it. I didn’t feel like there was a question of, how will they get along, or how will their chemistry be. I knew they would get along because they’d known each other and wanted to work together. Both of their spirits, or internal beings, matched those characters so well that it would be hard to think it wouldn’t sync up when they were on set. When the three of us got on Zoom a few times, just seeing them joke back and forth, I was like, oh, they’re going to be great. And then seeing them the first time on set, I was like, I just want to watch them, so I assume most people will as well.

Like Jockey, the film is about a time/place/world that’s vanishing. Did you consciously think about continuing to tackle that theme?

I’m going to be able to skip therapy this week—this is great [laughs]. It’s funny because I was talking to my wife about this the other day. I’m talking about a new film, and I was telling her that the new idea is, okay, a person in a vanishing world [laughs].I’m from the old South—from an old southern family—and I grew up around this heavy nostalgia. From the time you’re a kid, it’s draped over you from your family members. So it’s probably partly from that.Growing up and people describing a world that they think they live in that you don’t actually live in as you’re looking around, and the good and the bad of that.

There’s likely something else in my makeup as well that draws me to it. I do recognize that I’m exploring that in some way and trying to either make peace with it or just throw it out there. Maybe after five more films, I’ll have a better answer for you as to why that is [laughs].

It’s a timeless theme that somehow also feels relevant to today.

When I was reading the book, even though it was set in the past, it felt so prescient, and it felt so timely, with what Grainier was going through, and what we talked about a minute ago with AI. Even now, we’re contending with the idea that America might not last in the way that it has. The world order that we’ve grown up with and that we’ve known might not be here in even 10 years. A lot of times, I think we feel like the foundations of the world, or our lives, are stronger than they actually are in reality. What do you do with that, when they’re not as strong as you think they are? How do you find grace in that?

To go back to where we began, about how things don’t last, is the beauty of the movies that they do endure, and they shine a light on lives you wouldn’t necessarily know about and are, in some small way, amazing and illuminating?

We don’t know what’s going to last or not. If you look back at 19th-century literature, who knows if Jane Austen or Charles Dickens thought people would be reading their writing 200 years later.There is something about the movie that’s like, hey, nothing lasts, and yet everything is important. The movie itself is contending with that—if nothing lasts, then what’s the point of making a movie?

It goes back to the paradox of life: even if nothing lasts, you still have it, and you still have that moment, and there are all these things that we do in life that aren’t going to matter in the end, and yet you still put yourself into it, and they do matter, because they matter in this moment.

I really did want it to be an appreciation of a certain type of person, regardless of country or race or creed or gender, who worked their ass off their entire life and tried to build a life for themselves and led a beautiful life—and then isn’t celebrated. Yes, the movie, and all of us, might not last, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth doing, right?