Jocasta is finally alone with Oedipus, the man she knows at this point only as her husband. She tells him about being abused and impregnated as a 13-year-old by Laius, a much older man who will eventually become her husband and whose mysterious death is at the heart of Sophocles’ tragedy, now revived on Broadway as a “political thriller” (Studio 54, booking to Feb. 8, 2026).

Jocasta’s (Lesley Manville) voice—until this moment brisk and commanding—is suddenly shaky. A horrifying disclosure of a traumatic event is being excavated from the psychological gloam into piercing, wrenching light.

“I was three things: a child myself, the mother of a child, and the lover of a powerful man,” Jocasta says, Manville forcing every word out as if crunching gravel. “That rancid man was a dirty animal and a criminal, and when he became a dark-blue plastic bag heavy with fat and old meat, I did not cry a single tear for him.”

Manville’s speech is not only one of the most compelling moments in Robert Icke’s contemporary reworking of Sophocles’ play, but on Broadway itself this year: a supremely acted navigation of inner pain.

Manville, star of Phantom Thread and who played Princess Margaret in The Crown (recall that later-years scene when Margaret and Peter Townsend are reunited?), won a Best Actress Olivier Award for her role as Jocasta in London earlier this year and will surely be a contender for a Tony in New York.

Oedipus’ (Mark Strong) horror at what his wife endured leads to a cascade of confirmations of other awful facts—and the realization of the truths first voiced by the blind Teiresias (Samuel Brewer) that he would kill his father and sleep with his mother.

Oedipus’ obsessive search for truth, and the recurring motif of sight and blindness—Oedipus, who can physically see, is blind to the truth—is present and correct from Sophocles’ original (as is the riddle Oedipus must solve), but Icke has shifted many other elements of textual and physical furniture.

Icke’s Oedipus—just as with his other distinctive New York productions like Enemy of the People, which came with button-operated voting for the audience, and The Doctor—crystallizes how potently conceived theater can be, especially when imbued with the kind of vision practitioners like Icke bestow upon the artform. His productions are conceptually, purposefully bold, seductively watchable, and—however you respond to them—never safe or predictable retreads.

The setting for this play—originally produced by Internationaal Theater Amsterdam, in association with Roundabout Theatre Company—is the night of a modern-day general election (the country is unnamed, though the accents are British), in which Oedipus is a candidate pledging in an opening TV news segment to be the chief disinfector of the body politic if elected.

To that end, he is determined to uncover the truth of his predecessor Laius’ death. It will be two hours before both that truth and election result are known. A digital clock counts down from two hours to zero (and wait to see how thuddingly precise the actors have nailed that last second), which, as any 24 fan will know, brings a surface thrill to the enterprise. (Tom Gibbons’ sound design serves both an occasional tick-tock and constant foreboding background burr; the cable news-style video is by Tal Yarden.)

The exit polls show Oedipus on the verge of a landslide, and he returns to his battle-room HQ, a brightly lit, spartan office (designed by Hildegard Bechtler)—a locus of power described as home that meaningfully steadily gets stripped of all its furniture as the play continues—to await confirmation of his victory and to investigate Laius’ death.

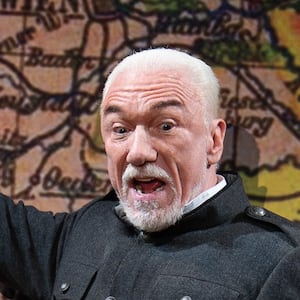

Strong, previously Tony-nominated for A View From the Bridge, is a commanding match for Manville—loving, impatient, laser-focused, desperate to be a good husband, father (supporting one son who comes out), and leader. But as Teiresias says, “There is nothing to be done, it is over.” Oedipus’ slalom to tragedy begins with his suddenly poisoned relationship with Creon (John Carroll Lynch), Jocasta’s brother and his campaign manager.

Oedipus’ mother Merope (a wonderful Anne Reid) wants to talk to him (his father is critically ill in hospital), while daughter Antigone (Olivia Reis) and Jocasta are at insult-lobbing odds; Antigone, like her father is searching for truth at all costs. Sons Eteocles (Jordan Scowen) and Polyneices (James Wilbraham) are goading and boisterous, and underdeveloped as characters. When a gun materializes, you know a shot will eventually ring out.

Alongside Jocasta’s speech, another on-point scene sees the family gather for a supper which blurs into a tumble of jocularity and vicious insults. Reid’s voice tolls like the play’s inner doom-bell, weary for having to ask for time for her son, and from the burden of past lies. She is also very funny. “Stop talking, Oedipus,” she begs when he goes TMI over his and Jocasta’s sex life. (Icke later explicitly shows just how randy the couple are for each other.)

The clicking clock and modern-day personal and political framing may make the show accessible and give it urgency, but its politics are also never fully fleshed out or followed through on. We don’t sense a country in any kind of state of decline. What is Oedipus’ vision, moral or otherwise, beyond truth-discovery? Are we, politically saturated beings as we are, merely having our cable news-consuming nerve endings toyed with?

Icke and his actors find the play’s real power in its traditional story. The scene in which Oedipus and Jocasta realize who they really are to each other—suddenly both with violently splintered identities—becomes a charged, terrible, so-very-wrong sexual ballet between the exceptional Strong and Manville. Concluding tragedies ensue, but in Icke’s version two questions are left intriguingly unanswered: will Oedipus lead this country, and if so what kind of leader will he be?