Carol Sturka (Rhea Seehorn) is a grouch.

She writes best-selling fantasy novels she thinks are junk. She has contempt for the fans who fawn over her at book signings. She loves her manager and girlfriend Helen (Miriam Shor) but is unsatisfied with her success, even having Helen rearrange her book’s position at an airport store in order to boost its visibility.

In general, she’s an antisocial downer whose every thought and word is colored by discontent. So when the world as she knows it comes to a sudden, terrifying end, she is, unsurprisingly, none too pleased about it.

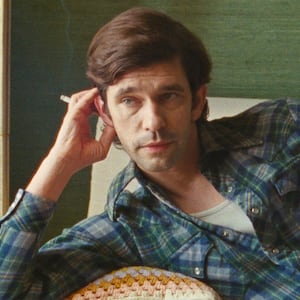

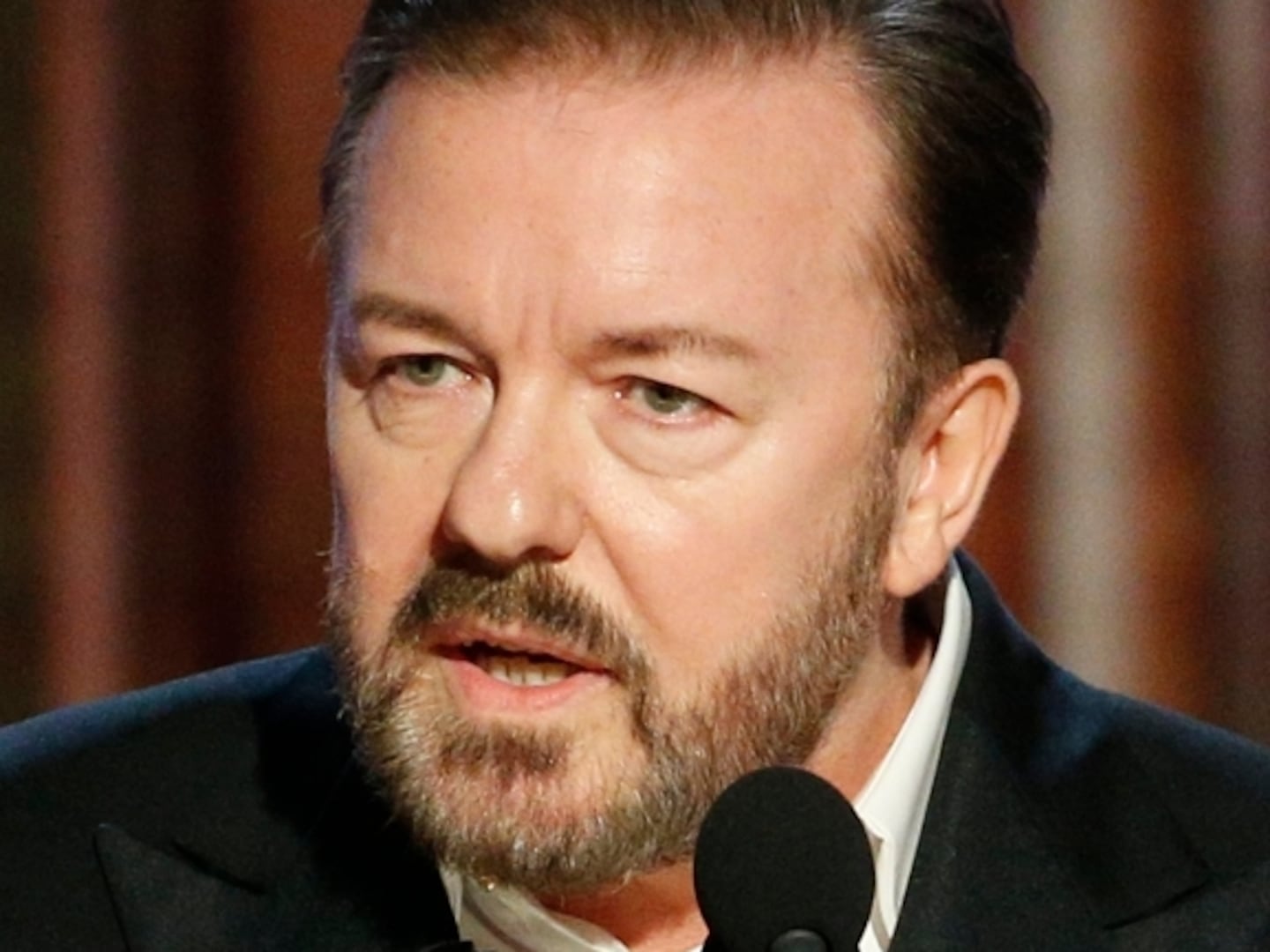

Pluribus, which premieres Nov. 7 on Apple TV+, is a story about transition that is itself the next phase of the career of Vince Gilligan following the tremendous acclaim of Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul. Aside from being set in Albuquerque and starring Seehorn, it’s a significant break from those celebrated predecessors, spinning a The Twilight Zone-ish sci-fi yarn that’s part Invasion of the Body Snatchers, part I Am Legend, and part zombie nightmare.

At the center of its madness is Seehorn as one of the few humans immune from the plague sweeping the globe, and the actress’ bitter fury is the prime source of both the series’ cutting comedy and aching pathos. With an icy stare that would chill the heart of any warm-blooded individual—which, unfortunately for her, are in short supply—she’s a furious force of nature in Gilligan’s latest, elevating his tantalizing mystery about the pluses and minuses of togetherness.

(Warning: Some spoilers ahead.)

Fresh off another triumphant book tour, Carol and Helen are on their way home when, while having a smoke outside a bar, Carol notices that the sky is covered in parallel streaks made by military planes. A second later, a truck crashes in front of them, the driver unresponsive and shuddering. He’s not the only one; as Carol discovers, every single person around her is exhibiting identical symptoms, including Helen.

With frantic purpose, Carol loads Helen into the crashed truck (since her SUV is locked due to a breathalyzer device, indicating prior DUI trouble) and speeds her to the hospital, where the same scene is playing out. With no help to be found, Carol strives to resuscitate Helen herself, and fails. At that point, everyone snaps out their twitching fugue, surrounds her, and attempts to kiss her. Then, in unison, they announce, “We just want to help.”

Carol responds to this madness by racing home, where she’s greeted by even more craziness. Her weirdo adolescent neighbors remind her where her spare key is, and inside, the sole broadcast on TV is of a suited official (Peter Bergman) at a White House podium, waiting patiently as a message repeatedly scrolls across the screen: “Carol. When You’re Ready You Can Reach Us at This Number. No Pressure. We Know You’ve Got Questions.”

That’s an understatement, and the answers she receives are far from comforting. As hinted at by the premiere’s prologue, 14 months prior, mankind detected an extraterrestrial radio signal from 600 light years away that provided a recipe for a virus-y “psychic glue capable of binding us all together.” Now, it’s done just that, linking humanity in a single hive mind—except, that is, for Carol and twelve other scattered people across the planet.

Pluribus establishes its premise with dawning horror-movie ominousness, and with every new revelation, its dread escalates. As is his trademark, Gilligan fleshes out his conceit via telling, evocative details, all while fixating closely on his protagonist as she tries to come to grips with this new world order and her place in (or, rather, outside) it.

Carol’s fear is matched only by her anger, most of it directed at the hive, who send—as a “chaperone” to guide her through this process—a foreign woman named Zosia (Karolina Wydra) who’s been selected because she resembles a character from Carol’s novels. As Zosia explains, the hive wishes her no harm; it wants to make her happy and is at her beck and call. It also, however, is interested in understanding what makes Carol special because its ultimate aim is to “fix it. So you can join us.”

Writing and directing the series’ stellar first two installments, Gilligan infuses the early going with unsettling intrigue, and the more he reveals, the more Pluribus taps into its fundamental concerns about individuality and community, and the irreconcilable paradoxes posed by man’s simultaneous desire to have agency and to be distinctive, and to find safety, love, and peace through unanimity.

In its own bonkers way, Carol’s plight speaks pointedly to man’s core warring impulses, and it’s those conflicts which power the action as the plot expands to focus on the other men and women who are resistant to the “Joining,” and whose attitudes toward this state of affairs are not necessarily in line with Carol’s irate and uncooperative stance.

Gilligan’s story is a knowing riff on various genre predecessors (Carol even references “pod people”) that nonetheless boasts its own set of interests, and it generates consistent unease from the flat cheeriness of the hive-mind population, which is capable of tremendous things—and holds the promise of bringing about a harmonious utopia—and yet is also obviously, fundamentally inhuman and, thus, untrustworthy.

The self and the group are at odds in Pluribus, whose tale is additionally about the costs of paradise, and whether they’re worth paying. With each subsequent narrative step, Gilligan complicates his scenario via his main character, whose defiance pits her against all of Earth and has unexpected consequences for her hive-mind compatriots.

Pluribus considers what it means to be human—thoughts, feelings, opinions, desires, etc.—and then wonders if those things are compatible with, or outweigh, the sort of ideal compassion, tranquility, intimacy, knowledge, and stability afforded by the hive.

With on-screen time markers routinely noting how long it’s been since the start of this cataclysm, the show is at once a ticking-clock thriller, a full-bodied character study, a philosophical rumination, and a unique vision of the immediate post-apocalypse.

Happiness may be as deadly as rage in this unsettling, unreal affair, but with both Gilligan and Seehorn in excellent form, there’s no risk—just reward—posed by its numerous pleasures.