The makers of Broadway musical The Queen of Versailles obviously hope their climactic visual reveal—a finished wing of Jackie Siegel’s ostentatious mega-mansion in the suburbs of Orlando, Florida, named after the famous French palace—will wow the audience.

Gold-trimmed everything, sweeping staircases, gleamingly symmetrical proportions and rendering: this bit of the house, in real life still under construction after over 20 years, is revealed in all its questionable splendor after nearly three hours of grimly ugly musical theater, and the shell of the set being shrouded in dustsheets.

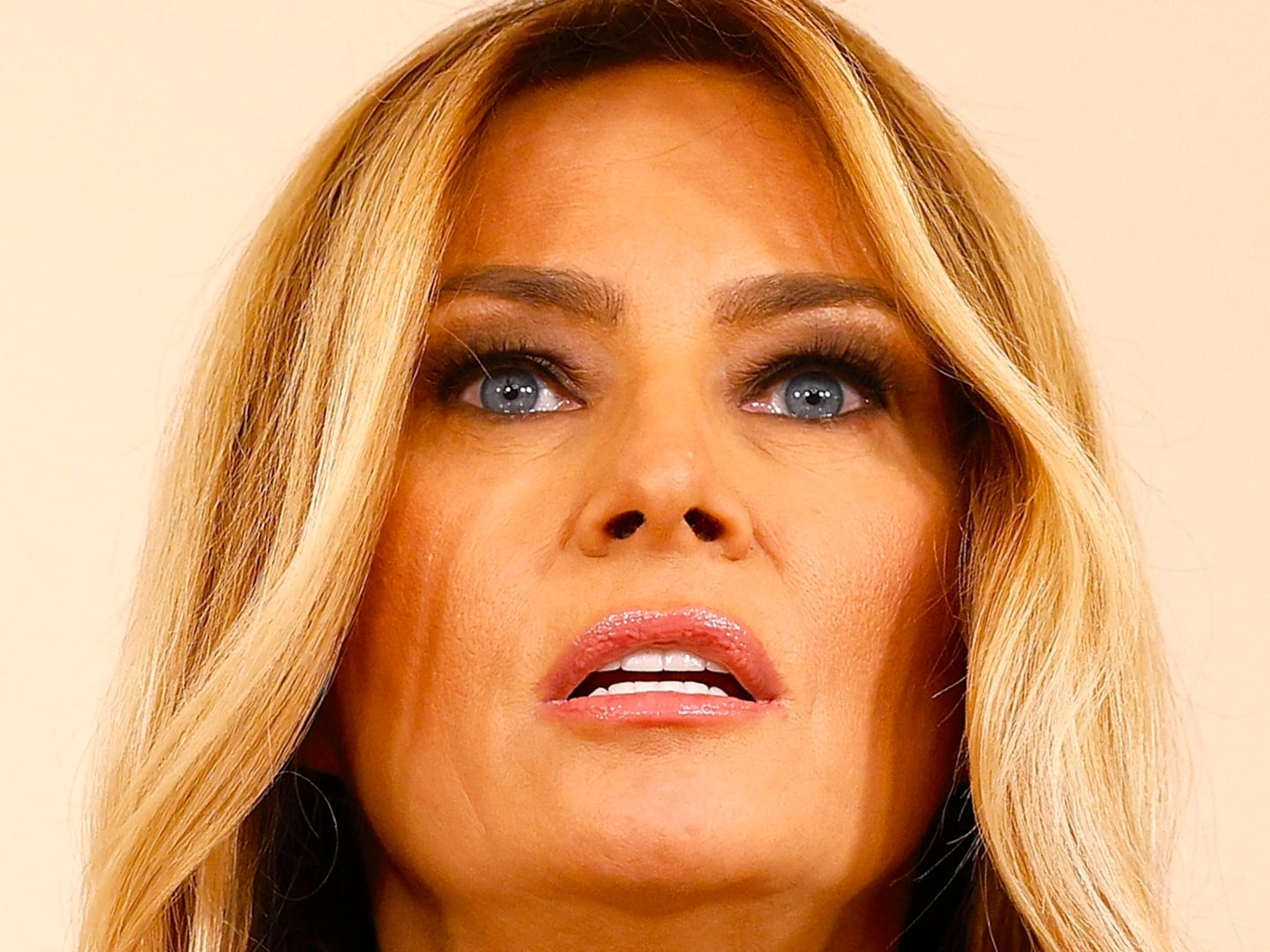

The audience, ours at least, wasn’t wowed. The palatial final vista feels as cold and empty, and as cheap-feeling and gaudily underwhelming, as the show itself—with Kristin Chenoweth as Jackie in a final sparkly frock lost in her own world of her-and-only-her, simpering in front of what seem to be Jackie’s favorite things in the world, a camera and lights.

(Jackie Siegel has financially invested in the show itself, though reportedly has no artistic control.)

As presented in the musical (directed by Michael Arden, with songs by Wicked composer Stephen Schwartz, and book by Lindsey Ferrentino), Jackie seems a soulless—not soulful or fascinating—avatar of extreme wealth and its discontents.

There is nothing exciting about the grand design of the mansion being part-realized, just as there is nothing heroic or arresting about the lead characters in this story, or the musical’s misguided attempts in trying to make them interesting (including an overuse of cameras and screens) as they relentlessly obsess over money, wealth, and crowing about and displaying that wealth.

The show barrels gracelessly through Siegel’s life story: modest upbringing, determination to succeed, sexism at work, more determination (especially to meet rich men), New York (Broadway tryouts), beauty pageants, abusive relationship (here, tellingly, the character of Jackie says she doesn’t want to dwell and the musical obeys), and then finally meeting billionaire husband, timeshare empire founder David Siegel (F. Murray Abraham) who sees everything in brute financial terms—and his wife and family barely at all, addressing them coldly and unpleasantly throughout.

We watch the warmth-free Siegels spend millions on building “Versailles,” the effects of the 2008 financial crisis (in a nutshell: they’re fine, and don’t give a damn about anyone who loses everything), the 2015 opioid overdose that tragically kills Jackie’s 18-year-old daughter Victoria (Nina White), and the disgust of Jackie’s niece and adopted daughter Jonquil (Tatum Grace Hopkins) whose indignance at Jackie’s behavior ultimately outweighs her initial enjoyment of living among its material riches.

We see and learn not much of Jackie’s grief at Victoria’s loss (apart from it being a springboard for a charitable initiative), we wonder about the many other Siegel offspring unseen as characters, and we eventually leave Jackie in the present-day all alone, still trying to finish construction on the mansion. (Outside the show, David Siegel died of cancer this year and Jackie’s sister, Jessica Mallery, died after overdosing on cocaine laced with fentanyl.)

Chenoweth fans will rightly appreciate that she sings loud and proud; she absolutely gives it, belts it, her all. But self-explanatorily titled songs like “Caviar Dreams, “The Royal We,” “Show ‘Em You’re the Queen,” “Keep on Thrustin’,” and “Because We Can” are ghastly, look-at-rich-me! anthems, and not catchy enough to even flicker as possible earworms.

Instead, they (and the script) revel in the worst kind of money-mad thirst at a time of many thousands are losing their jobs and facing immense hardship; a time simultaneously of massive inequality and the glorification of venality by a billionaire class when—as with Elon Musk’s recent trillion-dollar payday—the very rich seem only to become very much richer. No show can ever plan for the specific cultural moment it will appear in, but The Queen of Versailles lands with a particularly clueless, nauseatingly tone-deaf thump.

Some of its makers may claim the musical as satire or pointed analysis. But that would be a flimsy justification for a show that is, in the main, a celebration of the kind of spending and crude cashing-in on her “Queen of Versailles” status that Siegel has been famed for ever since participating in Lauren Greenfield’s 2012 documentary of the same name, and which first brought her to public attention.

Quite who Chenoweth is playing is as muddled as the story: Jackie as thoughtless capitalist monster, go-getting all-American hero, terrible parent, deluded Norma Desmond? Whatever, someone is clearly going for “camp” in the overall conception, hence the glittery dresses, leopard-print, and the spend, spend, spend excess of it all. But The Queen of Versailles isn’t camp. It’s cheap tat, queasy spectacle, grubby glitz. It doesn’t burrow beneath its surface wealth to ask anything of substance.

The characters in The Queen of Versailles seem greedy, immoral, and shallow, and never evolve beyond that. The family members are in constant, scratchy conflict, and not sharply observed in any way, even when it comes to the odd notes of texture like Victoria’s fury-infused songs around body image (“Pretty Wins”) and her feelings of general revulsion, as contained in her diary (“The Book of Random,” a number seemingly bussed in from Dear Evan Hanson).

The Siegels are also not imagined—if this was another aim of the makers—in a fun-exaggerated, grotesque way. Instead, the musical shoehorns glancing criticism of the family—Oh, look at what hyper-capitalism can do to people! The tragedy of a world gone money-mad!—but such moments feel like hastily added notes of contrition, especially when the musical has been brazenly gorging on Jackie’s compulsive piling-up of baubles for most of its duration.

This trace of critical self-examination contrasts sharply to the show’s bold display of its characters’ cravenness. (A trip Jackie takes back to her modest childhood home with Victoria feels an inauthentic attempt at grounding her character, as moments later it’s back to money-obsession-as-normal.)

In a secondary narrative, the show picks a group of aristocrats and royalty (Louis XIV and Marie Antoinette) from the French Revolution as an echo of the Siegels, presumably to show how the vacuously rich can sleepwalk to their own extinction (and because Jackie was inspired by the real Palace of Versailles).

However, the comparison makes little sense. The Queen of Versailles doesn’t come to vanquish the Siegels or skewer their beliefs and lifestyle, or to contextualize or condemn Jackie and the bubble of crazy she lives in. She doesn’t face any personal or moral reckoning; she just carries on. What she really wants, why she really wants it, and what this musical really understands about any of it remains firmly concealed under those dustsheets.