Given the current state of the union, it’s little surprise that Hollywood has turned to the bleak early books that Stephen King wrote as Richard Bachman—a pseudonym that allowed him to express his inner-most fury, bitterness, and hopelessness about man and the world.

However, whereas Francis Lawrence’s recent The Long Walk captured the meanness of its 1979 source material, Edgar Wright’s The Running Man is caught uneasily between the scathing satirical harshness of King’s 1982 tome and the goofy superheroism of Paul Michael Glaser’s 1987 big-screen version starring Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Largely faithful but unwilling to pick a funny or nasty lane, it’s the most impersonal film of its writer/director’s career, and a revolutionary thriller that too often falls back on establishment conventions.

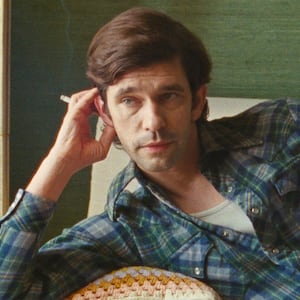

Narratively speaking, The Running Man (November 14, in theaters) sticks closely to King’s original, setting its dystopian tale in Co-Op City, where the haves live behind armed gates and the have-nots reside in slums where money is scarce, jobs are scarcer, and kids develop cancer at an alarming rate. Ben Richards (Glen Powell) knows these hard truths well, since he’s been blacklisted from working and his two-year-old daughter Cathy has a cough that can’t be remedied by the palliative meds he can afford.

Thanks to his dire circumstances—including the fact that his wife Sheila (Jayme Lawson) toils at a nightclub where prostitution seemingly runs rampant—Ben is the angriest man alive. Yet Powell’s powder-keg fuming comes across as something of a put-on; despite his attempts at suppressing his mega-watt charm, the actor is too likable to sell himself as a rageaholic.

Also handicapping Ben’s ire is the fact that The Running Man immediately establishes him as a good guy via the revelation that he’s lost multiple gigs due to helping others—a noble selflessness that’s as out-of-place in this run-down, hard-bitten milieu as Powell’s He-Man physique, which the film dutifully shows off during a later set piece.

The grittiness of Co-Op City and the desperation of Ben’s plight don’t suit Powell, and that’s additionally true of Wright, who stages his action with an excitability that squashes any sense of hardship, anguish, or recklessness. Nonetheless, for a time, the material’s pedal-to-the-metal energy keeps such concerns at bay, with Ben deciding that the only way to earn enough New Bucks (which are emblazoned with Schwarzenegger’s face, wink-wink) to get Cathy medical care is to sign up for one of the TV game shows that have contestants risk life and limb for cash.

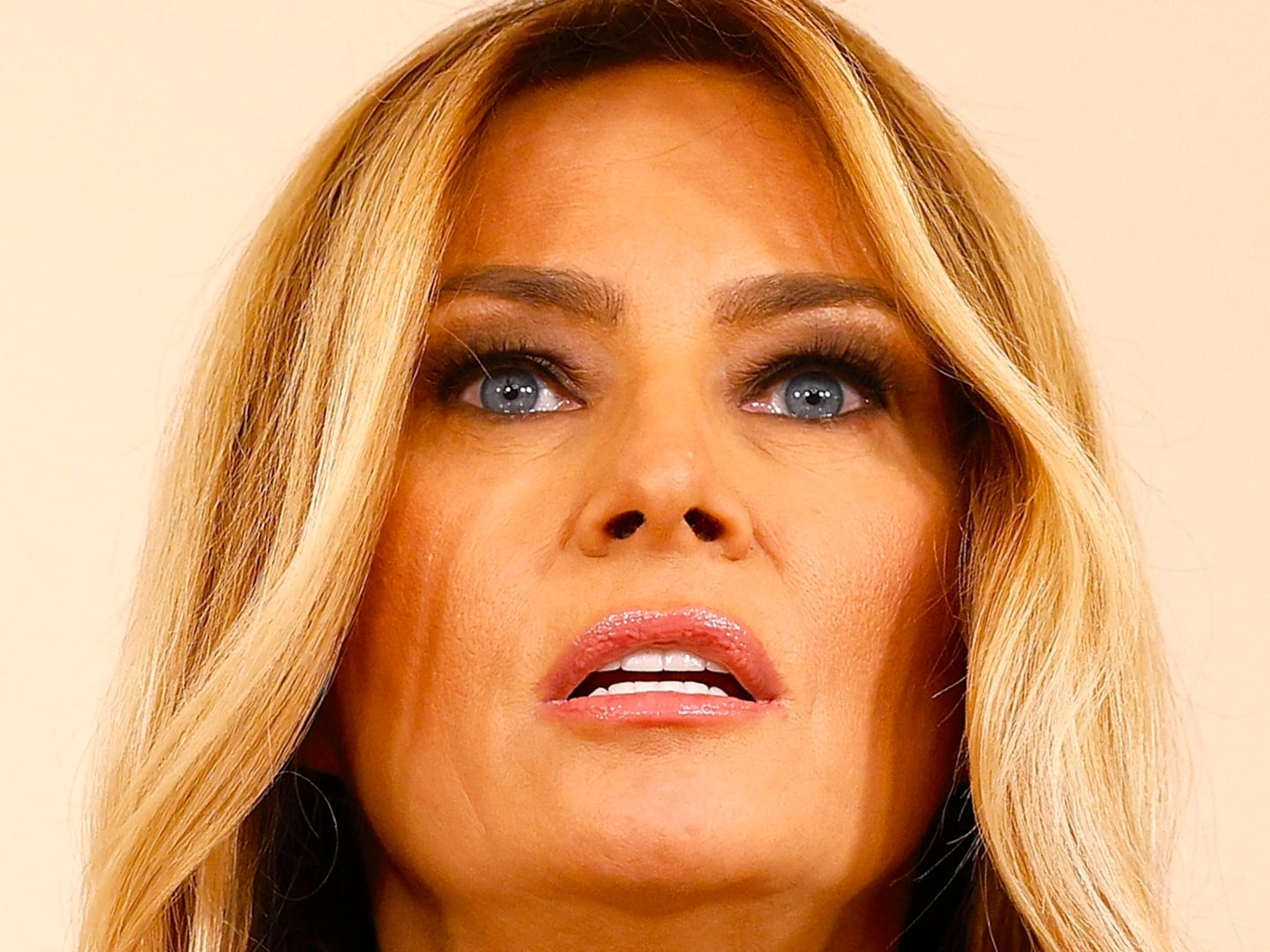

Ben promises Sheila that he won’t try out for The Running Man, the network’s most popular program, in which three down-on-their-luck individuals strive to win $1 billion by staying alive for 30 days as they’re stalked by homicidal “hunters.” The longer players remain breathing, the more their bank accounts swell, but because citizens have their own financial incentive for aiding the hunters (and viewers want to see blood), lasting a full month is virtually impossible. Ben knows this, and yet thanks to his uncontrollable temper, he’s selected for The Running Man alongside two similar saps (Katy O’Brian and Martin Herlihy) by producer Dan Killian (Josh Brolin), who views Ben as a potential superstar.

All of this hews to King’s novel, as does most of the ensuing plot, with Ben moving from city to city by donning disguises—a touch that more than faintly recalls Powell’s Hit Man—and keeping a low profile. In his quest, he’s aided by friend Molie (William H. Macy) as well as stranger Bradley (Daniel Ezra), who produces a series of anti-The Running Man online videos, and who views Ben as a possible insurgent “initiator” capable of bringing the system to its knees.

Still, there’s something overly cartoonish about the filmmaker’s approach which sabotages the proceedings’ righteous indignation at a society that unjustly demonizes the poor, exploits their suffering for entertainment, and manipulates, deceives, and kills in order to maintain its preeminent position in the class war it perpetuates. The ideas are all there, but Wright’s zippy direction renders them as superficial and unconvincing as Powell’s mad-as-hell ranting and raving.

The Running Man is occasionally amusing and frequently propulsive, complete with periodic knockabout skirmishes and shootouts between Ben and his pursuers. In both regards, though, that makes it feel too much like Schwarzenegger’s comic book-y predecessor.

The eventual appearance of Wright’s Scott Pilgrim vs. the World headliner Michael Cera as dorky dissident Elton only exacerbates this situation, providing a few minor laughs in exchange for genuine outrage. As The Running Man’s flamboyant host Bobby T, Colman Domingo hits the sinister sweet spot, going over-the-top in a way that oozes rancid, amoral ugliness. And Brolin’s turn as the villainous Killian is similarly assured, all arsenic smiles and salesman slickness. Like Lee Pace’s masked hunter Capt. McCone, however, they’re treated as mere cogs in a routine machine, making brief impacts before being cast aside for more of Powell’s strained seething.

Wright has always been a whiplash-inducing showman, so it’s deflating that The Running Man is lively without being aesthetically inventive. It’s fast and furious but lacking in visual or sonic imagination, such that Co-Op City looks like every other sci-fi metropolis from the past forty years, and its game-show spoofs feel like leftovers from RoboCop.

To be fair, King’s tale predates (and in many cases inspired) its hallowed genre brethren. Even so, there’s a rehashed quality to most of its elements, which include self-driving cars, drone cameras, and other surveillance-state apparatuses. More troubling, in the home stretch, the film loses whatever mild sharpness it initially possessed, having fake-out fun with King’s grim conclusion before opting for something more rousing.

The Running Man’s optimistic ending is designed to leave audiences feeling good on the way out of the theater—the exact opposite reaction sought by King, whose revolutionary fantasy was anything but rah-rah reassuring. It’s one more instance in which Wright sands his saga’s edges in order to comfort rather than confront, turning what might have been a harrowing vision of American boob-tube fascism run amok into a feel-good fight-the-power story that’s as trite as Elton’s Che Guevara print.