Much pop culture has flowed from the saying that Britain and America are “two countries separated by a common language.” The transatlantic clash of the brash and modest, the old and new countries, the deciphering of accents and words, the stiffly self-contained and let-it-all-hang out—with both sides of the pond cherishing and deriding the characteristics of the other—has been a longtime staple of books, movies, TV, and theater.

It’s also a lived experience for those Brits visiting or living in the States and Americans doing the same in Britain. At the beginning of the musical Two Strangers (Carry a Cake Across New York), British visitor Dougal (Sam Tutty) is trying to impress upon New Yorker Robin (Christiani Pitts) the beauty of iconic British savory spread Marmite—a food passion I not only share with Dougal, but like him have also tried to impress upon American friends. (With one pal I neglected to make clear the yeast extract spread should be used sparingly on toast; they spread on gloopy dollops of the stuff and made themselves violently sick.)

The familiar terrain of blunt Yank meets eccentric Limey comedy burns initially bright in Two Strangers, which was a big hit in London (from the small Kiln Theatre to the West End), and is now having its New York moment at Broadway’s Longacre Theatre (booking to July 5, 2026).

The show opens with an overlong segment contrasting British and American radio, which deflates on impact because they don’t sound so different. Still, it sets the culture clash theme. Robin has come to JFK to meet Dougal. Her sister and his dad are getting married, he has arrived to attend the nuptials. But Dougal was expecting to see his dad (for the very first time), and Robin is doing a favor for her sister with whom she has a testy relationship.

Dougal is a not-snazzily dressed, curious-in-manner goofball—inappropriate, slightly creepy but not threateningly so, crazy about all things American. Robin is a Black, direct, firmly focused New Yorker, who thinks he’s just a weirdo with no sense of personal space, and far too wide-eyed and strange for her to want to spend any time around. He wants to do all the tourist stuff; she balks at the idea. “I’m walkin’ here!” he recites joyously.

But—and I think you can see this coming—for all their differences, Dougal and Robin discover they are very much alike—both are not wealthy like his unseen dad is, and they are hiding pain rooted in their familial relationships. The musical mulls whether Dougal and Robin’s fledgling friendship could become a romantic relationship.

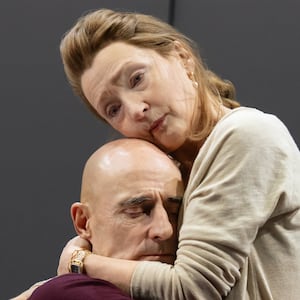

“Two Strangers” is funny in places, occasionally moving in others, and just a little off-feeling throughout, as if it is trying too hard to charm across the storytelling and whimsy chasms it creates for itself. Its flaws are not fatal, thanks to the singing skills, charm, and likeability of Pitts and Tutty who generate the right kind of tricky, rather than star-crossed, chemistry. (Can and should a would-be step-aunt and nephew really get together?)

The title of the show, directed and choreographed by Tim Jackson, is a bit of a misnomer. While it’s true that Dougal and Robin do indeed pick up and carry her sister and his dad’s wedding cake, it is not “across New York,” by any means. But an accident involving the cake does mean an extension of Dougal and Robin’s journey in and around the city, and themselves, in search of resolution, wider truths, and personal freedoms.

In a great song set at the coffee shop she works in, Robin imagines a life away from serving others. Dougal relishes the idea of finally getting to know his absent father—even though, early on, we can see that his father is avoiding the same. And soon we learn why Robin’s sister is so freely exploiting Robin’s time, and why the sisters are at odds.

Jim Barne and Kit Buchan’s story is played out on a strikingly designed, minimal set: an unattractive double mountain of suitcases on a rotating stage, colored a mummified grey. From and within these suitcases spring colorful eruptions of objects, signifying where the duo are, like the Plaza Hotel or (the loveliest-realized setting) a noodle restaurant.

The suitcases also light up to signify New York buildings and its streets. Perhaps symbolically they represent the emotional baggage all humans carry, as well as the journeys people are on in a more profound sense than just physical transportation. Whatever, the cases look imposingly ugly, and act as a creative handcuffs on the show. In a smaller theater they might look charming, on a Broadway stage they are an inadequate visual anchor.

The musical packs a more precise punch charting the grittier realities of Dougal and Robin’s emotions. It is very funny when Dougal rightly identifies Robin as his kind-of-new-auntie. It is sad when he realizes the truth about his dad, and it is also puzzling that he is so in the dark about it all pre-landing in America; Robin’s relationship with her sister is also under-explained and underwritten. The show is beautiful when it explodes with an old-fashioned song-and-dance number (“American Express”), the pair dressed to the nines, sweeping Fred-and-Gingerishly through the city for one night of expense and extravagance.

Two Strangers is on shakier ground as it orbits the possibility of romance between Dougal and Robin. Here, their chemistry and show’s intentions feel confected. The duo seem more natural as two opposites who (despite his romantic liking for her) find a platonic simpatico through pain, and a shared determination to chart a path through it. Their not getting together, the joy of their unexpected friendship, make most sense. Dougal and Robin are definitely a couple to root for—just not together.