All eyes are on Broadway, as the big, starry convoy of Tony Award-eligible productions’ opening nights continue to roll by. But avert your gaze from the bright lights for a moment. There is another Washington in town besides Denzel in Othello; his daughter Olivia is giving a truly electrifying, must-see performance at the Classic Stage Company as Tommy, the lead character in Alice Childress’ terrific, heart-punch of a play Wine in the Wilderness (through April 18).

The play, directed by LaChanze—Tony-nominated actor, producer, and president of Black Theatre United—is both political and personal in focus. It is 1964, Harlem, and the sounds of a riot reverberate from outside: police sirens, shouting, flashing squad car lights. The present-day audience member’s mind immediately flicks to the unrest of more recent times.

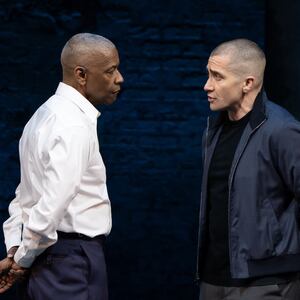

The apartment/artist’s studio in front of us—Arnulfo Maldonado’s design is delightfully evocative, with lighting by Jeanette Oi-Suk Yew—is owned by Bill Jameson (Grantham Coleman), whose interest is not in the social unrest outside, but in finishing the triptych of the play’s title; little does he know it, but the model he finds will challenge his views on art, women, and race.

The play was not first presented on a stage, but by television station WGBH in Boston, Massachusetts, on Mar. 4, 1969, as the first play in a series “On Being Black.”

LaChanze’s commitment to ensuring Childress’ work is staged is steadfast. She starred in the similarly excellent and thought-provoking Childress play Trouble in Mind (1955) when it finally, far-too-belatedly premiered on Broadway in 2021. The reason Trouble in Mind didn’t premiere on Broadway in Childress’ lifetime—she died in 1994, aged 77—was because producers wanted her to rewrite it to make it more palatable to a commercial audience. Childress refused.

As Jill Rafson, the CSC’s producing artistic director, writes in the program for Wine in the Wilderness: “Childress was an actress who didn’t see roles being written for Black women like her, and she didn’t see stories on stage that reflected her world and the questions that her community was facing every day. So she wrote them herself.”

Childress’ name remains (absurdly) not as well-known as it should be. As both plays show, she was writing pieces interrogating big themes—race and gender—that feel on-the-nose contemporary.

In Wine in the Wilderness, Bill is aiming to sketch the final panel of the triptych. In his apartment is Oldtimer (a standout Milton Craig Nealy as a roguish-seeming community elder), more interested in seeking to hide some riot-night loot he has come by.

Bill helps him, while revealing his artistic progress: the first triptych panel shows a young Black girl in Sunday dress and hair ribbon (as a symbol of innocence), the second shows what Bill sees as a feminine ideal—a vivacious, dramatically dressed figure called “the Wine in the Wilderness.”

Tonight, Bill hopes to fill the third panel with the figure of “the lost woman…as close to the bottom as you can get.” His friends Sonny-man (Brooks Brantly) and Cynthia (Lakisha May) have supposedly found a model out in the riots—born and raised in Harlem “but backcountry” enough to convey whatever the vision of debased womanhood he has in mind. Bill relishes the idea of his masterwork being complete, and of the acclaim and awards that will follow—Grantham imbues him cleverly with both a lazy arrogance and quicksilver charm.

Bill’s groovy friends (the groovy 1960s costuming is by Dede Ayite) escort a woman named Tommy (Washington), who is not arty, and who talks a mile a minute with free use of the N-word (the group asks her to use the phrase “Afro-American” instead). She isn’t much in the mood for any niceties; the riot has destroyed her home, “All I got is gone like it never was.”

However, Tommy makes it clear she is “not lookin’ for a meal ticket. I been doin’ for myself all my life.” Cynthia notes Tommy is brash, which isn’t surprising as she’s had to look out for herself. But she adds how diminishing this can feel to men like Bill; she should give back Black men’s manhood to them, she says. Tommy rightly snaps back that she never took it from them in the first place.

It is Bill’s hypocrisy that reverberates most loudly as he impatiently tries to get Tommy ready to model; she wants Chinese food, he appalls her by serving up a frankfurter. He criticizes her for not being feminine enough, then says that “Black is beautiful.” Tommy—who reveals her real name is Tomorrow Marie—replies she doesn’t feel that beautiful given his tone of voice with her.

As the modeling session begins, Tommy removes her hair-piece (wig and hair design is by Nikiya Mathis), and a different side of her is revealed: Washington transforms Tommy from emotional loudspeaker to someone calmer, her sharp and wry intelligence upending Bill’s expectations and behavior towards her. (Soon he says if he was smart as her he would wake up singing every morning.)

Having misunderstood how he sees her—she hears him talking on the phone in laudatory terms about the second figure in the triptych, and thinks he is talking about her—Tommy inevitably discovers she is there to model as a down-and-out vision of Black womanhood.

Furious, Tommy confronts Bill anew, not only standing up for herself but also calling him out for his own misogyny and anti-Black racism. This leads Bill to reconsider his art, representation, and the final panel he wants to produce, using Oldtimer, Sonny-man, and Cynthia, with Tommy at their center. The final moments of the play evoke a new, pluralistic vision of community and history which will be memorialized on Bill’s canvas. Tomorrow Marie is showing them all a way forward to the conventional future-meaning of her first name.

From her wig to what is rendered as Bill’s art, from preconceptions of a person to their real self, Childress is fascinated by all kinds of presentation, of wrongfooting us as to who her characters are versus how they are seen, and where these complicated, air-breathing, blood-pumping humans lie on the broader, sweeping timelines of history, beyond stereotypes, media invention, and simple platitudes.

Like Trouble in Mind, Wine in the Wilderness is itself a canvas of a moment in time, with—just as Bill finally paints—people captured as who they are right then. It is a beautiful piece of writing, and in LaChanze’s clever direction and her excellent company of actors’ hands it is freshly transformed—nearly sixty years after it was written—into a drama that, while rooted in the past, feels current and urgent. Long may the rediscovery of Alice Childress continue.